The Last Glass

The flame has been extinguished in the glass workshop at Aarhus University. After 37 years, Jens Christian Kondrup has retired as the last scientific glassblower at a Danish university.

With his right hand, Jens Christian (Chris) Kondrup holds a small glass flask in the intense white flame of the burner, rotating it steadily until the glass glows. Now, it’s ready for him to blow, stretch, or mould into a multitude of new forms.

But that would require both hands, so he sets the flask down on the table and turns off the burner. This was just for the photographer.

Chris Kondrup suffered a stroke over a year ago, and despite intensive rehabilitation, the sensation and fine motor skills in his left hand and fingers are not what they once were.

At the end of September 2024, he ended his career as Denmark’s last scientific glassblower. He has already closed his private glassblowing workshop, where he used to make glassware.

A Successor Wanted!

The workshop at the Department of Chemistry, however, will remain intact. The department is searching extensively for a new glassblower, especially abroad, since people with Chris Kondrup’s skills are extremely rare in Denmark.

"The workshop and service environment created at the Department of Chemistry is unique among Danish universities. You need to go to foreign universities to find anything comparable," says Chris Kondrup.

This is why he is a member of the Verband Deutscher Glasbläser (VDG), where his job title is glasapparatebauer (glass apparatus maker). In Germany, approximately 70 such professionals are trained each year for universities and industry.

“There’s no equivalent training programme here. I recently attended the VDG’s three-day conference in Kassel, where I advertised the open position at Aarhus University,” Chris Kondrup explains.

He fondly calls his colleagues in the association his “glass family,” having known them for over 30 years.

“It’s a solitary job, so you have to absorb everything you can when you’re out in the world,” as he says.

Good Chemistry with Researchers and Students

In the Chemistry Department workshop, he has not been completely alone. Chris has worked closely with researchers, Ph.D. students, and other technicians at the university.

As a scientific glassblower, he hasn’t merely followed researchers’ specifications to create glass tubes, flasks, containers, etc. – he has actively participated in their development.

“Over time, I’ve learned a lot about chemistry and reactions. So, when researchers and students came to me with a problem, I helped them develop a solution, often through multiple prototypes. It was a pleasure since it sparked creativity in both me and them,” says Chris Kondrup.

“A glassblower needs to understand their material; there’s no single correct or incorrect way to do it – it’s the result that counts. I loved seeing the light in students’ eyes when I showed them how their ideas could become reality. And it was great to watch them rush back to the lab with the finished piece to continue their research,” he adds with a happy smile.

An Asset for Research

Chemistry Professor Troels Skrydstrup has collaborated with Chris for many years, mainly through the support Chris provided to his Ph.D. students and postdocs.

“Chris showed genuine interest, helped with development, and assisted them. This allowed us to stay ahead in our research and develop innovative solutions in chemical synthesis,” says Troels Skrydstrup.

According to Skrydstrup, Chris Kondrup’s talent for making glass pieces that perfectly fit research needs has been a significant asset for scientific research – not only for chemists at Aarhus University but also for researchers worldwide.

Glass Reactors a Hit

This is especially true for the double-chamber glassware Chris Kondrup developed in 2011, which he later produced in various versions for a Danish company that continues to sell it to universities and the pharmaceutical industry worldwide. Now, production is handled by a foreign factory.

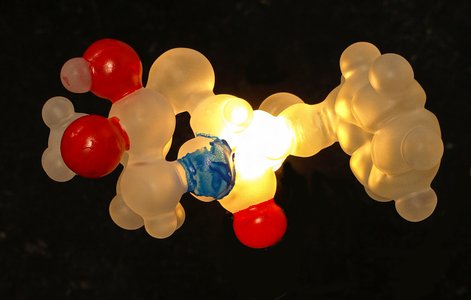

The double-chambers look like two test tubes connected by glass bridges and serve as dual-chamber reactors for conducting chemical reactions with toxic components, like carbon monoxide, under safe conditions.

“The clever part is activating a toxic gas in one chamber, which diffuses into another chamber to interact with other substances. The quantities are small enough to be safe. Since 2011, we have published nearly 90 scientific articles that incorporate this double-chamber reactor,” explains Skrydstrup.

Chris Kondrup takes pride when he sees that a researcher he helped has secured a grant.

Chris Back in the Saddle

Glass was both Chris Kondrup’s profession and hobby. He became interested in creating art after taking courses in the USA and Venice around the turn of the millennium, exhibiting his work in places like the Ebeltoft Glass Museum, the Aarhus Art Building, and the Steno Museum.

When Queen Margrethe presented the Danish Craft Award of 1879 in 2002, it was Jens Christian Kondrup who received the bronze medal.

Now, Chris Kondrup has returned to another hobby in which he also excels: cycling.

After the stroke, it’s now called paracycling – competitive cycling for people with disabilities.

“I’ve been cycling for many years. Thanks to the rehabilitation at the Hammel Neurocenter and municipal programmes, it took just five months from my hospitalization to the first time I sat on a racing bike again. I dreaded ending up in a nursing home when I was in the hospital,” he says.

This summer, Chris Kondrup placed second in the Danish Paracycling Championship.

A Blessing in Disguise

Then there’s the story of how the double-chamber reactor came to be.

One day, the valve on a carbon monoxide tank in a 5th-floor lab at the Department of Chemistry malfunctioned, releasing the gas.

Carbon monoxide is a colorless, odourless gas that, when inhaled, displaces oxygen in the blood and can be fatal.

Troels Skrydstrup recounts:

“A student came down to my 4th-floor office, sounding the alarm, and we immediately evacuated. We ran down to Chris, who was then our safety and fire inspector. He went up with breathing equipment and shut off the valve.

We couldn’t allow this to happen ever again, so we decided we would no longer work with carbon monoxide tanks. That’s when the idea emerged to generate carbon monoxide from solid material in a chamber within a chamber, in such small quantities that it’s perfectly safe. Chris developed several prototypes, and there it was.”

Facts

Jens Christian Kondrup trained as a glassblower at Struers A/S in Copenhagen from 1981 to 1987 before joining Aarhus University.

He worked with a glassblowing technique called flameworking, which involves shaping pre-made glass rods and tubes by partially melting them over a 2000°C flame. Only a handful of people in Denmark use this flameworking technique.

You can find Jens Christian Kondrups own farewell post on LinkedIn here (in Danish)

and you can reach him at jkondrup.glas@gmail.com, when he's not out biking.