Nathalie Wyss and Novo Nordisk have joined forces to develop more specific and improved antibodies. This could make Novo Nordisk's work cheaper and more efficient. In the long term, it is hoped the project will lead to fewer side effects and that less medicine will be discarded during development.

By Ida Dengsøe

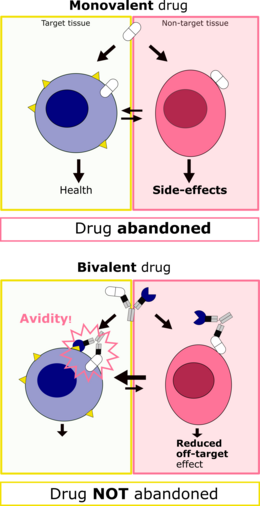

We currently lack more in-depth knowledge and more streamlined processes in work on antibodies for pharmaceuticals. We need to understand how an antibody can become stronger and more specific by binding with two arms instead of one.

Nathalie Wyss from the Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics has made this the focal point of the industrial PhD she is currently working on with Novo Nordisk. She hopes the project will make a real difference for the pharmaceutical industry.

"We're working on a more focused method that we hope will save both time and money. This could make it easier to develop new drugs, and save some that are not currently good enough in the early stages," says Nathalie Wyss, who has been working on the project for more than two-and-a-half years.

The phenomenon is called avidity, and it describes how an antibody binds to its target. Supervisor and Associate Professor Magnus Kjærgaard from the Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics uses the gym to illustrate the so-called bivalent antibodies in the project.

"Imagine hanging on a wall bar with one arm, compared with hanging there with two arms. Clearly you’ll hang there more firmly if you use both arms. The same applies to antibodies," he says.

Furthermore, there is good potential to improve the current method, explains Charlotte Wiberg, who is the principal supervisor on the PhD and the principal scientist at Novo Nordisk:

"The entire project stems from the challenges we face today in predicting the effect of avidity during the development of pharmaceuticals, and it is time-consuming to find the perfect medication. We need more in-depth knowledge about the specific parameters we need to look for. It has become a kind of screening by trial-and-error," she says.

Among other things, the parties involved in the industrial PhD are working together to develop a platform technology and an algorithm to make it easier to develop bivalent antibodies. The aim is to arrive at a more accurate process in the future, explains Magnus Kjærgaard.

"The process needs to be more streamlined, so we know more about what actually works. We hope it’ll be cheaper to produce and develop new antibodies, because fewer incorrect designs will have to be tested."

If the project is successful, according to Charlotte Wiberg it may make a big difference for Novo Nordisk.

"In the long term, we hope that this will make work on developing pharmaceuticals more efficient and ultimately save a lot of time," she says.

It may also have a number of advantages in relation to side effects, says Nathalie Wyss.

"Many new drugs have the disadvantage that they have different side effects, but I hope that my project will help to reduce some of these side effects," she says.

It may also be possible to save pharmaceuticals that would previously have been discarded during the start-up phase because they have too many side effects, or because they miss their target.

"Perhaps you want to target the liver, but not the same receptor somewhere else in the body. More knowledge about this area could help us to save more potential candidate medicines," explains Charlotte Wiberg.

Magnus Kjærgaard shares this hope.

"Just changing the success rate from one to two per cent would be a huge result," he says.

The PhD is not aimed at one specific disease, but may have significance in the areas such as diabetes and its complications; the area Novo Nordisk specialises in. There are also potentials within cancer and obesity, says Magnus Kjærgaard.

"Precisely this more general focus makes the PhD project so useful. We’re trying to take a step back and study a more general problem that covers all antibodies," he says.

Staff at Novo Nordisk are used to collaborating with PhD students in the laboratories, and Charlotte Wiberg is in no doubt that she would recommend the programme to other companies. According to Charlotte Wiberg, the collaboration between the university and the students is inspirational, and it helps provide new perspectives, insights into other workflows and, not least, the opportunity to take a more in-depth approach.

"We’re always looking for closer contacts with the leading researchers in our field, and this just isn’t possible without some degree of collaboration. I think this kind of ongoing exchange of ideas and discoveries between us and the university is crucial," she says.

For Nathalie Wyss, the collaboration means that she has become colleagues with many talented specialists, and she has access to other resources and tools. But most importantly, she has obtained a crucial insight into the practical realities of industry.

"I knew that I wouldn't stay in academia all my life, and I wanted to go into industry. I enjoy being able to experience the dynamics of a company. It's important for me to get a little closer to patients, and that my research can make a difference in the practical reality – even if this is only in the long term," she says, adding that it can also be a challenge to reconcile inputs and needs from the university and the company.

"They don't always have the same objectives. The university often wants good research articles, while industry is more interested in optimising or developing new methods. You can be a little torn at times, and you have to learn to make your own decisions."

For AU Supervisor Magnus Kjærgaard, it is particularly beneficial that a programme like this gives the two parties a better understanding of each other.

"You can be sitting on your chair at university and think that you’re looking at an important problem for the pharmaceutical industry. But when you actually talk to them, you might find that they’re thinking about something completely different. The challenge is to find a good project that generates enough benefits for a company for them to invest money in it, but that also generates enough knowledge and recognition to make it interesting from a research perspective. It has to make sense for both parties," he says.

Nathalie Wyss plans to complete her PhD project in 2023.