What can we learn from the climate challenges of the ostrich?

The ostrich is an obvious model for investigating how large animals are affected by the large fluctuations in temperatures we will experience in the future. This is what postdoc Mads Fristrup Schou thinks. He has received an ERC Starting Grant of €1.5 million, and next year he will set up a new research group at the Department of Biology at Aarhus University.

The research project is about understanding the evolution of animal tolerance to cold and heat. The question is whether the genes that increase the heat tolerance in an animal also reduce its tolerance to cold.

Mads Fristrup Schou has received €1.5 million from the European Research Foundation to find out. He is currently a postdoc at the University of Lund, and he will use the grant to establish a research group at the Department of Biology at Aarhus University.

> Starting Grants from the ERC are awarded to researchers who, at an early stage in their careers, have contributed excellent research, demonstrated a talent for working independently, and exhibited potential to manage a research project.

> To put things into perspective, a new-born human baby weighs on average 3-5 per cent of what an average adult weighs. When an elephant calf is born, it usually weighs only 2.2 per cent of what it will weigh ten years later as an adult.

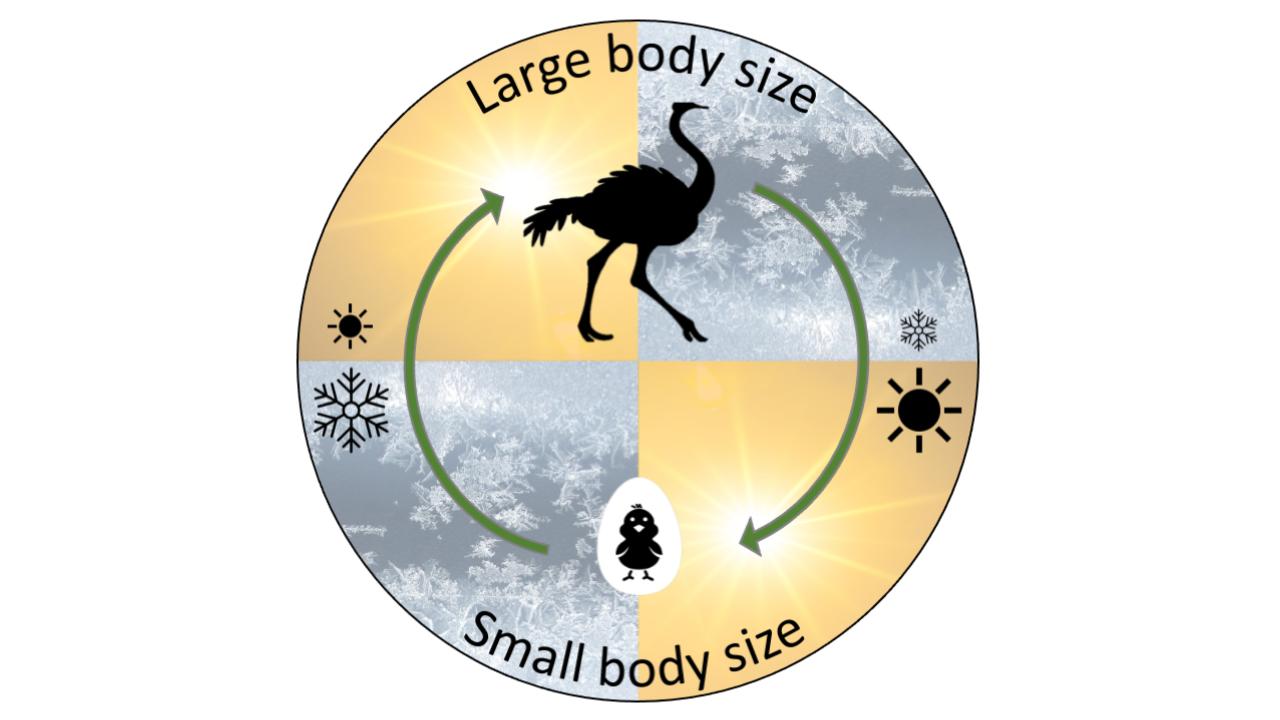

The questions are very relevant in light of climate change and increasing temperature fluctuations. And they are particularly relevant with regard to large animals, because they are particularly challenged by temperature changes. Large animals often have the biggest differences in body size from young to adult.

This is a challenge, because temperature fluctuations affect individuals differently as they grow. A small body is sensitive to cold because its surface area is large in relation to body weight. On the other hand, it is more resistant to heat. The opposite applies for a large body: it has a hard time dealing with sustained heat, but fares well in the cold.

And here, as a warm-blooded animal, the ostrich is an excellent model. A newly hatched ostrich weighs just under 1 per cent of the weight of an adult.

Furthermore, the ostrich lives and breeds in the Kalahari desert (where temperatures can vary between 40°C and below freezing), and in temperate regions like the Cape of Good Hope on the southern tip of Africa. This means that the ostrich can provide an insight into the demands of extreme environments.

"This project will give us an understanding of how large animals adapt to temperature fluctuations and the life stages that set the limits for this adaptation. As things stand, we don’t know whether heat and cold tolerance are genetically linked. A negative correlation would mean that genes which increase cold tolerance in young individuals reduce heat tolerance in adults. If so, there would be a heat-cold trade-off across the life stages. What life-stage should a species then prioritise when evolving to persist in even greater fluctuations?" says Mads Fristrup Schou.

Contact:

Postdoc Mads Fristrup Schou

Email: abumadsen@gmail.com

Mobile: +45 5134 9299